For a writer of well-received international mystery thrillers, Chris Pavone can sound hilariously parochial. As a dutiful househusband in Luxembourg — the exact location of which he had to look up on a map — Pavone struggled with the oven dials because they were written in German. (He’d studied French in preparation for the move.)

A day trip to Germany to buy a clothes dryer for their apartment was a bust. (“We were unprepared for how much German there’d be in Germany …”).

No matter. After a month of working with a clothesline in the guest bedroom, Pavone discovered that the washing machine was also a dryer. He found out as he was translating the two-dozen settings on the machine. One of them said “Dry.” (What? Not “trocken”?)

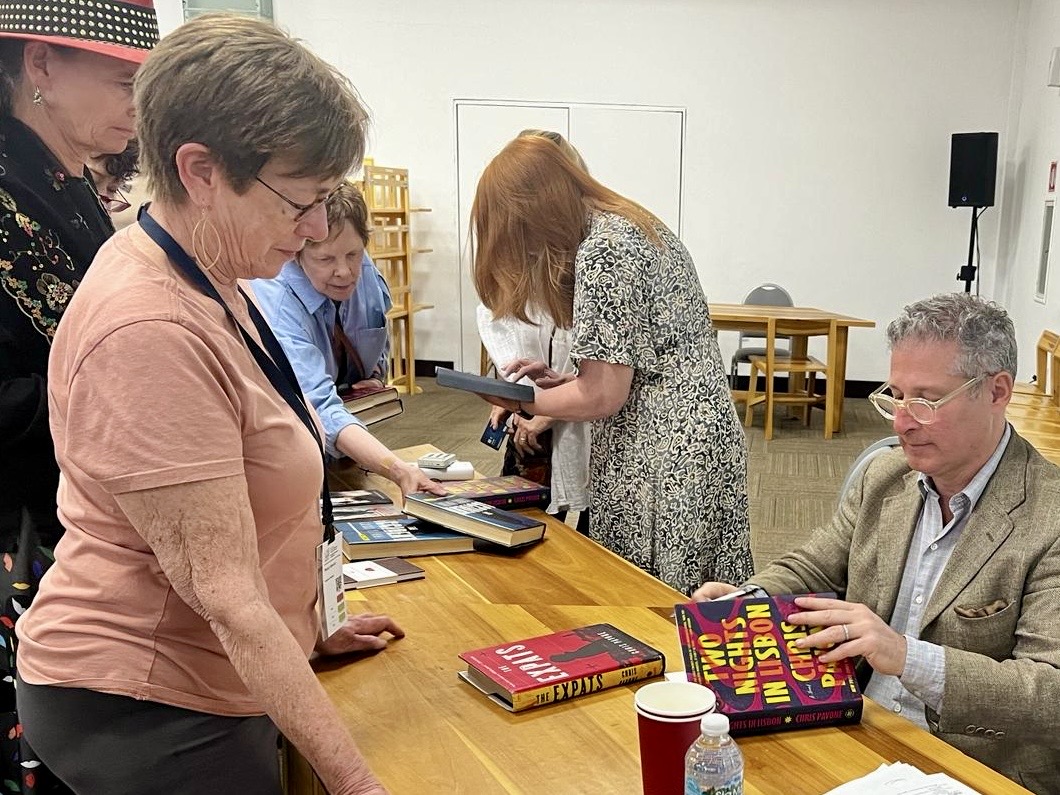

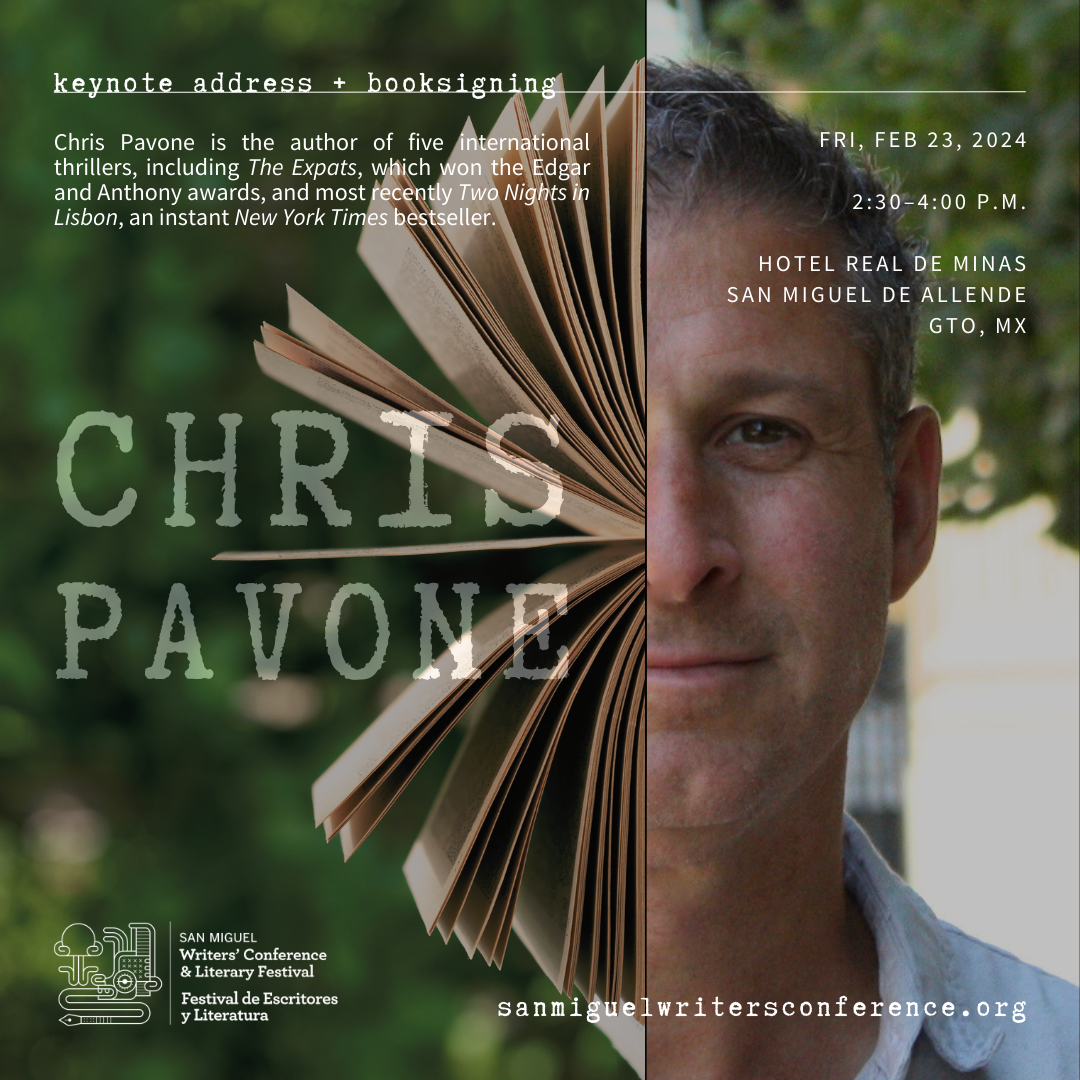

I’m thinking this tale got a pretty good laugh on Friday afternoon at the San Miguel Writers’ Conference where Pavone was the final keynote speaker of the weeklong conference at the HRM hotel.

I say, “I’m thinking” because I didn’t make it to the talk. Pavone almost didn’t make it either. He had a mean case of laryngitis earlier in the week and so he printed out his speech so that others could deliver it. By Friday, Pavone was well enough to deliver the goods. And I’ve been lucky enough to have been loaned the goods.

Damn, I wish I’d been there. For an international best-selling thriller writer, he sure can write.

The speech is nicely structured into three parts, focusing on three of his five novels, and in each, he reviews the bits in his life that lead up to the writing of each.

The first is, as you may already have guessed from the lead-in, The Expats from 2012, his well-received debut novel. Kate Moore is a stay-at-home mom who has coffee with other moms, drops the kids off at school, and generally struggles with the same exasperations of all highly competent people who are unchallenged. Mind you, this is all taking place in Luxembourg.

And cheer up, Kate’s secret past as a State Department operative catches up with her — just about the time that she discovers that nothing and nobody around her is as it or they seem. Kind of your classic unraveling of a “deadly conspiracy with immense global implications.” Only done really, really, well.

Pavone and his family moved to Luxembourg just before he turned 40, after a career in publishing that went from copyeditor to executive editor to deputy publisher in a number of New York publishing houses. In Luxembourg, Pavone’s wife had the job. He got the kids. And “meting out discipline, grocery shopping, cooking, cleaning, walking the dog … but mostly just parenting, all the goddamned time.

“I’d been a grown-up with a career, I put on suits and ties and got my shoes shined on the way to the office. I had meetings, I was a New York book editor, and I’d invested a lot of myself into becoming that.

“Now who was I?”

No surprise that Pavone nails Kate Moore’s “life of quiet desperation” in The Expats. He was living all the “alienation, the loneliness, the frustrations, the existential angst: ‘Who am I?’ of being a new ex-pat and a stay-at-home parent. He discovered that many of the at-home moms that he hung out with were in similar straits.

Desperation can be the mother of invention.

An especially unfriendly — hostile even — woman in a park one day jump-started Pavone’s imagination. Here in Luxembourg, the banking, governmental, and espionage center of the world — “So maybe this woman was a spy? … Maybe her husband was the spy?”

Ladies and gentlemen, the birth of a spy novel.

“Most spy novels are, fundamentally, stories about betrayals within intimate relationships,” says Pavone, “with larger than life consequences — prison or freedom, life or death, war or peace. Most domestic suspense is also about betrayals within intimate relationships.

“I’d long wanted to write a novel,” he added. “And this, I realized, was one I could write: a spy novel that’s also a novel of domestic suspense.”

A year into life in Luxembourg, Pavone “went straightaway to a cafe with my laptop. I opened a new file, and typed The Expats at the top of the page.”

The rest is international best-seller history with the much-prized Edgar and Anthony awards attached.

Kate Moore returns in The Paris Diversion, published seven years later. (In between, Pavone published The Accident and The Travelers.)

It started out as a 9/11 novel and not just because everyone was writing a 9/11 novel. Pavone lived through the terrorist attack: a front-row seat of every horrific moment from his TriBeCa loft. When the World Trade Center towers collapsed, the force shook his building. He was evacuated and couldn’t return home for months. That close to Ground Zero.

The smells. The ruble. The armed soldiers. The people leaping from the towers. The cloud of dust. The chaos. All of it was seared into his brain. Hardwired into his consciousness. “At the time, I didn’t recognize PTSD,” he says.

Fifteen years later, he went to Paris to write a novel based in Mexico. In 2016. He entered his second world of terror and chaos.

“France was reeling from a series of brutal terrorist attacks — on the Charlie Hebdo magazine, on the Bataclan nightclub, and just a few weeks earlier on a Bastille Day celebration in Nice that killed nearly 100 people and injured 500 more. In Paris there were soldiers everywhere, bomb-sniffing dogs, a general mood of tension, of fear,” he recalls.

He adds: “This felt familiar to me. … This, I realized, was my 9/11 novel.”

“But a novel that uses the threat of terrorism to manipulate perceptions of what’s going on, as real-world terrorism does. To manipulate not only the characters within this book but also manipulate its readers.

“This novel would be about terrorism used for unexpected goals. Perpetrated by unexpected villains. Villains who look a lot more like the author than anyone else.”

That Mexican novel would have to wait.

It took only a few months to write the first draft of The Paris Diversion.

“But it also took 15 years,” he said.

And if you think you know what this story is about …

“You’re wrong.”

The choice to go into publishing, rather than be a published writer, was a conscious one for Pavone. He knew the “low-odds choice” that writers faced.

He took the safer road.

On that road, he met the likes of esteemed authors John Grisham and Pat Conroy and got to work on some of their novels.

Prior to this, Pavone was a bit of a literary snob — “a young man with a young man’s taste in literature with a capital L — Nobel Prize winners, Pulitzer finalists, short stories in magazines that would never dream of hiring me. I didn’t read best sellers.”

You live. You learn. Especially after editing his share of Grisham blockbusters.

“Those Grisham thrillers changed the way I looked at commercial fiction, and opened my eyes to the idea of creating suspense against a background of important issues — toxic pollution, the death penalty, big tobacco, sexual assault.”

He spent a month “helping Pat Conroy bring a novel called Beach Music to the finish line.”

What a novel that would make: a way overdue novel, a problematic author ensconced in an Upper East Side hotel room rewriting it in longhand, a young buck assigned to babysit the writer and keep him focused until it is finished.

“That babysitter was me,” recalls Pavone.

The two of them would take long walks in Central Park. “Pat was a tremendous talker,” recalls Pavone, “but he was also a prodigious listener, constantly quizzing me about my childhood, my life, my everything.”

Finally, Conroy dropped a gem on the aspiring author: “‘Listen to other people’s stories, Pavone. Listen carefully.'”

“It turned out that is why he’d been quizzing me,” he said. “Because he’d been working. Because being a novelist isn’t something you only do when you are writing. It is something you do all the time.”

It is a lesson that has shaped Pavone’s career as an author.

“Like Pat Conroy advised, I’ve listened to the stories around me, all the time. And because my life has been populated largely by women, theirs are the stories I’ve heard the most, the concerns I’ve cared about the most, the tragedies that have hit me the hardest.

“Like John Grisham, I’ve tried to set human-level drama against societal-level issues.”

The third leg on Pavone’s stool is a lifelong love for puzzles. He loves Danielle Trussoni’s new novel, The Puzzle Master. He once edited books of puzzles. The Thursday crossword puzzle in the New York Times is his favorite which contains a “tricky theme within the puzzle.”

“Those are the novels I try to write,” he said, “with a puzzle within a puzzle, to create a surprising paradigm shift, and ultimately a tremendously satisfying payoff.”

That said, Pavone’s latest novel Two Nights in Lisbon brings all these lessons and intrigues to the fore. Not surprisingly, Pavone calls it “the best of my five novels.”

“The initial spark was the Access Hollywood tapes” on which Donald Trump bragged about assaulting women as if it were a sport. Surely, he thought, that was the end of Trump as a politician.

As we all know, that was not so.

“I watched in abject horror, as half of America shrugged,” he said.

“I don’t begrudge anyone their honest political beliefs,” Pavone added. “But surely there’s no pro-rape political party.”

By the time Supreme Court candidate Brett Kavanaugh came along — a “touchy privileged misogynist who’d pretty clearly committed violent sexual felony,” Pavone had sunk “into a funk of despair about what’s wrong with America, about what could be done about it.”

Kavanaugh got the robe. Pavone got the inspiration for his best novel yet.

It is a thriller about a woman whose new husband suddenly vanishes but the target could well be the hermetically sealed culture of men who see life and their relationship to women as Trump and Kavanaugh do, through the eyes of a certain kind of sexual privilege.

“That’s what Two Nights in Lisbon” looks like, at first: a story about an American man who goes missing while on a business trip in Lisbon,” says Pavone. “It’s really a novel about something else entirely.”

And remember that Mexico novel Pavone set aside to write The Paris Diversion?

Last week he was in Mexico City and thinking about a CIA novel based in Morocco. Sure. Why not?

While walking on Paseo de la Reforma, a wide avenue that crosses the heart of Mexico City, Pavone pulled another switcheroo.

“If anyone has any friends at the embassy (in Mexico City) who are willing to meet with me, please get in touch,” he told the audience.

He left them with a final bit of literary wisdom: “It all comes from somewhere.”

(Photos by Mary Finley)